Jacques Marchais Coblentz was born in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1887. According to Marchais, her father John Coblentz chose the male name, ‘Jacques Marchais’ – a family name of importance to him before her birth, and did not change it to the feminine form of Jacqueline after she was born. Her father died when she was a small child. Jacques Marchais was a precocious child and her mother, Margaret Norman Coblentz, put her on the stage as a child elocutionist. She used the stage names Edna Coblentz and Edna Norman to avoid confusion about her “masculine” name and used her earnings to support herself and her mother. Her acting career began in the Midwest and at the age of 16, she was cast in a Boston production of George Ade’s play, “Peggy From Paris,” where she met her first husband, Brookings Montgomery. They eloped and had three children, two daughters, Edna May and Jayne, and a son, Brookings, Jr. The marriage was short-lived and the children went to live with their paternal grandparents in St. Louis, MO. In 1916, she relocated to New York City to support herself as an actress and resumed using the name, Jacques Marchais. Jacques Marchais – The visionary behind Staten Island’s Shangri-la.

While in New York, she surrounded herself with a circle of friends who shared a common interest in art, spirituality and Buddhism. In 1920, Jacques Marchais married Harry Klauber (1885-1948), a Brooklyn-born entrepreneur in the chemical business. Jacques and Harry moved to Staten Island in 1921, and settled on Lighthouse Hill, where according to her diary they could have “a farm within commuting distance of Manhattan” and she began to collect Tibetan art.

Inspiration If I can give the world something that would be uplifting and a genuine help, perhaps, I should try. –Letter to Kate Crane-Gartz, 1933.

Jacques Marchais Tibetan Art Gallery

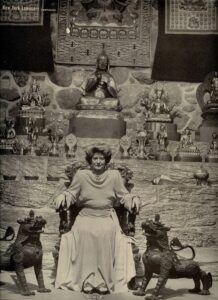

Jacques Marchais developed this affinity for Tibetan culture in the late 1920s and thoroughly studied all she could. She believed she “was more or less acting as a magnet in drawing East Indian and Tibetan deities and ritual objects.” After viewing an exhibit dedicated to the Chinese Lama Temple Potala of Jehol, at the 1933 Century of Progress International Exposition in Chicago, she became particularly inspired to enhance her collection of Tibetan artifacts and share her knowledge with the world.

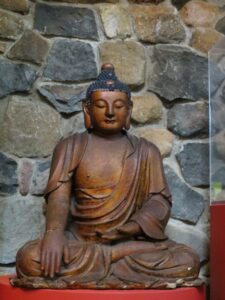

In 1938, she opened the Jacques Marchais Gallery to exhibit art from the relatively unknown cultures of East India and Tibet. The collection ranged from extravagant artwork and thangkas upon the wall to carved wood furniture and light fixtures. Statues and sculptures lined the shelves, as Marchais proudly showcased her acquisitions to groups and individuals alike. Many of these artifacts only became available to collectors like Marchais from 1911 – 1950, due to heightened political activity in the region. She desired to impact humanity on a larger scale and used the gallery as a “stepping stone” to building the Museum.

Although she never traveled to Tibet, she acquired items through auctions and estate sales. Marchais would often keep the best pieces for herself and sell other objects in the gallery as a means to continuously build her collection. She was committed to sharing her knowledge of Tibet with the world.

In her lifetime, Jacques Marchais amassed a collection of over one thousand objects. The collection includes sculpture, ritual objects, musical instruments, thangkas or scroll paintings and furniture. The objects are primarily from Tibet, Nepal, northern China, and Mongolia, and a few items are from Southeast Asia.